In the 1990s, the Cameroonian feyman Donatien Koagne made himself famous for his scams, in particular the multiplication of banknotes. It consisted "of making rich suckers believe that they had a top secret way to turn white paper into dollars. […] The prey [is] invited [to] a private session intended to convince him/her of the efficiency of the process."1 The scam is simple and clever, and works better when the greedy customers are gullible. Even if the terms differ2, one inevitably thinks of the banknote scam in the first chapter of For Love of Imabelle. The date, however, prevents seeing the Cameroonian feyman as the inspiration for Himes. Indeed, the latter wrote For Love of Imabelle more than 30 years before his exploits. Conversely, could Himes have inspired Koagne? In other words, did the scam the naive Jackson fell victim to existed or was it invented by Himes? It will undoubtedly be difficult to answer this question. As for Donatien Koagne, did he invent the banknote multiplication scam or did he simply dramatically develop an existing practice?

On the other hand, the connection with Cameroonian scams is interesting for two reasons. "Faced with the model of the ‘opponent’, ideal of the youth of the years 1991 to 1994, the feymen embodied, in collusion with the ruling class or manipulated by it, that of corruption, illegality, and easy money."3 Let us remember the hatred that Grave Digger and Ed Coffin feel for crooks, while they do not bother, for example, "the owners of serious brothels, the managers of serious gambling houses, those in charge of underground lotteries and prostitutes who stay in their neighborhood"4, considering them as necessary for the needs of the inhabitants and the cohesion of Harlem.

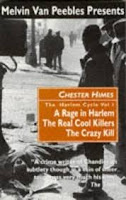

Moreover, for Himes, the scam often has an African origin: thus Dr. Mobuta (Mobutu?) and his remedies against infertility (Blind Man with a Pistol), as well as the fake African doctor in rags that Sugar embodies in The Crazy Kill. The description of Sugar, dressed in a nightgown and a towel tied in a turban, and his words denote a vision of Africa as a land of superstitions and crude magic, a repulsive image of black origin. "This oil," Sugar continued, "is made with the fat of male kangaroo claws mixed with the essence of the productive organs of lions. It will make you jump like a kangaroo and roar like a lion."5 Besides petty scams (the rise in the value of banknotes or the title deeds of lost mines), the scam can take on a whole new dimension. "The religious crooks (For Love of Imabelle, The Big Gold Dream, The Crazy Kill) exploit the fervor of the Blacks, transmitted by their ancestors, to enrich themselves and perpetuate the existing order. The political crooks, whether they advocate the return to Africa, black power, the black Jesus or interracial fraternity deceive the messianic hope for the liberation of Blacks. Himes twice discredits the return to Africa, always marked since Marcus Garvey with the seal of the swindle (The Heat’s On, Return to Africa)."

Africa as the cradle and essence of the scam?

1 Dominique Malaquais, "Arts de feyre au Cameroun", in Politique africaine, 2001/2 (N ° 82), p. 101 to 118, https://www.cairn.info/revue-politique-africaine-2001-2-page-101.htm. Alain Mabanckou and Abdourahman Waberi, Dictionnaire enjoué des cultures africaines, also devote an article to feymania, Paris, Fayard, 2019, p. 154 and following.

2 In For Love of Imabelle, the crook doubles the value of each note; Koagne multiplied the number of notes.

3 Dominique Malaquais, "Arts de feyre au Cameroun", op. cit.

4 Chester Himes, The Big Gold Dream, chap. 10.

5 Ibid., chap. 11.

6 Sylvie Escande, Chester Himes, l'unique, Paris, L'Harmattan, 2013, p.167.